W

hen you’re Bad Bunny, elevators are a careful maneuver. At any point, as the bell dings, you might be recognized, and when you happen to be the most-listened-to Latin artist on planet Earth, the statistical probability of running into any kind of fan — hardcore followers, casual listeners, excited tourists — is pretty high. It’s not that he minds, it just makes things slightly more complicated when the Puerto Rican superstar is trying to get from Point A to Point B.

So that explains why one bone-cold morning in New York, just two days after Christmas, Bad Bunny is facing the wall in an elevator heading to Rolling Stone’s offices. He’s head to toe in a simple pewter-gray sweatsuit, and as an extra precaution, the drawstrings of his hoodie are pulled so tight that you can see only a tiny sliver of his forehead, looking more like a faceless Pan’s Labyrinth creature than a sought-after, history-making, megawatt celebrity. The visual here — his team of about seven people standing next to a silent six-foot figure with his back to everyone — is almost comically weird, but it’s a smooth ride up without interruptions.

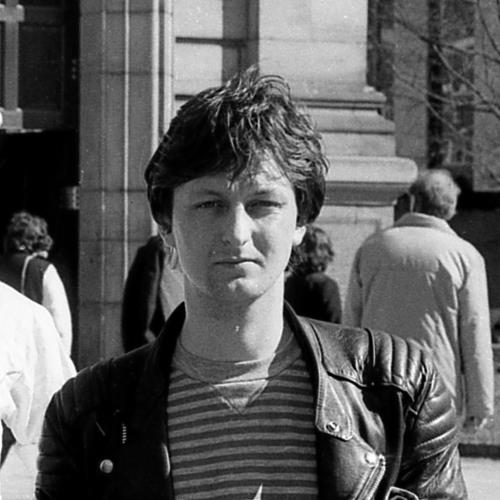

Ten floors later, the hoodie comes off, and there’s Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, bearded with his hair slightly grown out, bouncing around, looking through the past few issues of the magazine. He has thoughts: Looking at the October 2024 edition with Chappell Roan, he explains that a hairdresser on a movie set recently turned him on to the rising pop phenom. “She has, like, a Lady Gaga, Lana, Sia vibe,” he says. “She’s cool.” Turning to the January 2025 issue with Coldplay’s Chris Martin, he jokes, “I’ve always said he reminds me of a dolphin, and this cover in the water confirms that Rolling Stone and I are connected.”

He doesn’t want either of the two issues with his face on the front. (His first Rolling Stone cover was in June 2021; his second followed two years later.) The copies he asks for, instead, are Megan Thee Stallion’s issue from the summer of 2022, or something with vintage Shakira from the Nineties.

Though he’s known for being slightly reticent in interviews, today, Bad Bunny is fully charged and bursting with stories. Part of that is because he’s had a lot going on the past year: films, activism, moves across the country. More important, for the past few months, he’s been sitting on a new album called Debí Tirar Más Fotos, a stunning piece of work that makes him prouder than any of the multiplatinum smashes that preceded it.

There’s a deeper feeling to it all, almost like this album led him closer to what he wants to do. It’s a culmination of sounds and ideas that are grounded in folk and roots traditions from Puerto Rico, the rest of the Caribbean, and the wider diaspora. There’s salsa, there’s bomba, there’s trio — all bits and pieces of his childhood that he brought with him as he went from a teenager bagging groceries and posting songs on SoundCloud to a global superstar. He’s almost vibrating with joy as he talks about everything he learned from making this music.

“I enjoyed it a lot, but at the same time, it also went by so fast,” he says. “That’s why I think I’m going to keep recording songs — I don’t have to release them. But sharing ideas, watching kids play and enjoy music, it was so beautiful that I’d do that every day. I’d go to the studio every single day to make a new song.”

Last time we talked, you were living in L.A. So, compare the two — New York or L.A.?

Puerto Rico.

If you had to choose …

I like New York because it’s closer to home. L.A. feels very far away. Sometimes that’s good because you want to disconnect, and in L.A. it can feel like you went to another galaxy. But if I had to pick, if someone said, “You have to live in one,” I’d stay here. Although, L.A. has more Mexican culture. I started eating tacos birria, which are the best. In Puerto Rico, we found this really good tacos birria place from a family who is Mexican and Puerto Rican and raised in Dallas.

Your new album is called Debí Tirar Más Fotos [I Should Have Taken More Photos]. Where did that name come from?

It comes from me hating photos [laughs]. I started getting that reputation of not liking photos because sometimes I don’t feel like taking a photo with a fan if I feel like creating another kind of moment. And I had this reflection of, “Maybe I’m so used to photos with fans, and it’s not as special a moment as it is for the person who just saw me and who wants to save that moment.…”

But it has more to do with the way that sometimes there are these moments I live through, and I enjoy them, but I didn’t take any photos. I have a good memory, but I know there’s going to be a time where I’m not going to remember really incredible times. It has a lot of meaning in terms of wishing I had seized certain moments. That’s the idea: enjoying the moment when I could and valuing memories.

Photograph by Christopher Gregory-Rivera

Photos capture history. Nowadays, people can take photos of whatever, but before, I remember photos used to be so special. I remember my mom was always taking photos. When there was a birthday or some kind of event, you’d take like two photos and then you’d save them for the aunt who was 90 years old or when so-and-so was coming by with her new baby. They were for something special. When you revealed them, it was an event. The whole family would sit down, and we’d pass them around and be like, “Whoa, look at this!” It was about reliving those moments. When I got older, I would get so mad when Mami would take photos, because she was crazy about taking them, and now it’s the opposite. It’s like, “Damn, I wish I had a photo of this,” so it’s all those nostalgic feelings of valuing these moments and being grateful, beyond the photos. The album is also a reflection of how when you’re far away, you appreciate things more and you understand them better.

A few years back, you co-wrote El Playlist de Anoche, an album for the piano player and singer Tommy Torres. He said at one point that he felt your trap and reggaeton songs could easily be translated into ballads or pop songs.

I think my voice and my delivery is something I try not to change because it feels like it’s me. I could sing in whatever flow, but I want people to say, “This is Bad Bunny.” All those songs I made with Tommy, I could have made them, and they would have been great, but in Tommy’s voice, they sound more badass. I think it’s a question of the times, too. In another era, I would have practiced and taken vocal lessons. For the old people who are going to criticize me, I would have been a great composer — I say that humbly. Because I know how to adapt to any time. There’s a line on [my new salsa song, “Baile Inolvidable”] where I go, “The new girl sucks it well, but it’s not your mouth.” I know the old people are going to be like, “He ruined salsa!” But if I don’t put that in, it’s like I’m imitating [someone]. I could have put something super poetic in there — although that line sounds poetic coming from me [laughs]. But I feel like no matter the era I had been born during, I would have been great.

What was it like making a salsa song?

When I listen to it, I’m like, “This is the best song I’ve ever made in my life.” It’s a dream come true, because I’ve had this song in my head for such a long time. The synth you hear in the beginning, I first heard that when I was making [my 2022 album] Un Verano Sin Ti, and I said, “This is a salsa song.” But because the album was already so full of different things, I said, “I’m going to leave this for later.” I spent almost this entire year making it.

How did it come together?

Man, I can pull up the voice notes of me singing over the synth line and then going tan, tan tan tan, all the parts. And I kept being like, “How am I going to make this song a reality? I’ve never made salsa. Who do I look for?” I didn’t want to go to the same composers, I wanted to go to someone new. And in the most random way, we found this kid who’s starting to work as a reggaeton producer. He’s 24, but he comes from music school, and what he likes to do is musical arrangements. We found him because my friend Pino saw a story where he uploaded that Bryant Myers song “Narcotics,” and he made it into a salsa just to fuck around. They took it as a meme, like “ha, ha, ha,” but I was like, “Meme? Ha, ha, ha? This is insane. This is better than the original.” When I started working on the album, I was like, “Let’s invite that kid.” He was super quiet. His name is Big Jay because he’s super tall.

I was here in New York, and I kept being like, “Do we have the musicians? I need to get [to Puerto Rico] and start working because we’re short on time.” They started sending me people and I’m like, “This guy is good, this guy I’m not sure about.” And then on TikTok, I see this kid who was about 14. He was with this band of kids playing, and he was dancing and playing bongos. I was like, “Damn, he looks like a baby Roberto Roena! Find me this kid.” And they were like, “We can’t find this kid.” I called [my manager] Noah [Assad], and he was like, “I think the best thing to do is find a musical director. We found this guy who’s good. Plus, I think you sent a TikTok of this kid.” I was like, “Nooo!” He turned 19 when we were making the song. He was in charge of finding the musicians, and in the end, they ended up being musicians Big Jay had also recommended. They all knew each other. And when we started making the song, it was the coolest experience. Almost all of them are from La Escuela Libre de Música from Puerto Rico: Julito, who’s the one who turned 19; the trombone and the trumpet player are [in their twenties].

It was fully School of Rock.

Exactly!

“WHEN YOU’RE FAR AWAY, YOU APPRECIATE THINGS MORE AND YOU UNDERSTAND THEM BETTER.”

To you, what’s the best old-school reggaeton? What do you find yourself going back to?

These days, I’ve been listening to a lot of Hector Y Tito, like from 2002, A la Reconquista. I feel like reggaeton from 2002 to 2003, now that we know that reggaeton exploded with “Gasolina” and all that, I think the reggaeton from that period is what I value the most: Don Omar’s The Last Don, Tego Calderón. But that Hector Y Tito A la Reconquista, too.

Hector Y Tito have been kind of forgotten in a way.

Yeah, life decisions you make can take a toll. Just like Willie Colón went crazy, and he made badass music. You can’t take that away. But that era of reggaeton, 2001, 2002, that was the sweet spot. Or at least, it’s what you said — what I go back to. But it also depends on the season and my mood. Sometimes I want to hear stuff from when I was in high school, like 2008, 2010.

You’ve been exploring film, too. You’ve acted in four movies at this point: Bullet Train, Cassandro, Darren Aronofsky’s Caught Stealing, and Happy Gilmore 2, with Adam Sandler. What have those film experiences been like?

Badass. I worked a lot — too much. I did a week for Caught Stealing, and as soon as I finished, the other one started, which was Happy Gilmore. I was on set for 40 days, and then I went to Puerto Rico. So, I basically just had the 24th and 25th [of December] off.

Those last two movies couldn’t have been more different.

[Laughs.] Yeah, one is here, and the other is here [points in two different directions]. But I enjoyed that — I like that they were so different. And I can’t wait for them to come out for people to say, “Whoa.” I think with the projects coming up, I can focus more on only making movies.

Would you ever just be an actor?

I’d do it. I’m always going to make music, but I’d spend some time just making films and dedicating myself to acting. I think the way I worked it out, when those two movies get released — when people see them, they’ll say, “Wow, this guy is really acting.” Because it’s two different movies, two different parts, two different people. Even physically, I had to dye my hair red and shave my beard for one movie; for the other one, I had to dye it black. Everything is different. With Bullet Train, when I come out, it’s like, “Oh, Bad Bunny is coming.” It was like, “Bad Bunny stepped out of the studio to drop by [the film].”

You played more of a character in Cassandro.

That’s true. In that one, it was more of a role. But not a lot of people saw that the way they saw Bullet Train, which was on Netflix and had Brad Pitt. I would love people to see [Cassandro], though, because you can see it’s more of a character. And in these two, it’s the same: You can see I’m working and acting. It’s like, “Damn, this is a character. This isn’t Bad Bunny.”

What do you like about acting? How do you see it fitting into your career?

I’ve loved it since I was a kid. Actually, my mom didn’t know I was making these movies, and when I told her, she was so happy. She was like, “You have no idea how glad it makes me to hear these things. When you were little, even though you loved music, I never imagined you’d be a musical artist. I always imagined you as an actor. When you were little, I used to say, ‘This boy is going to be an actor.’ I never said, ‘This boy is going to be a singer.’ And to see you doing these things makes me so happy.” And I was like, “Whoa, Mami had never told me that, that she saw me as more of an actor.” So, it’s something I’ve loved since I was a kid, even though I was pretty timid.

Yeah, you’ve said in the past that you were shy as a kid.

Yeah. When I was little, I couldn’t explore those things as much. I didn’t sing in public. I sang, like, twice in school, but I was dying of fear. And I never did a lot of performances, just maybe a few things at church. I was never in a play at school or anything like that. But I did like it. When I was alone in my room, I’d act by myself. Everything that I would play, I’d always imagine I was acting.

Did you vibe with Adam Sandler when you were on set together?

Pshhh. That’s my uncle. Adam Sandler is my uncle. Look [shows text-message inbox, where Adam Sandler is listed under “Tío Sandler”]. He’s Tío Sandler. He’s super nice.

Another side of your career has been participating in WWE events. You started making appearances in those back in 2021. Would you do it again?

I want to do it one more time. I want to put my life at risk in the ring. I felt like I didn’t risk it enough in the ring, and I want to do it. I want to scare my mother. When? I don’t know. We stay in contact with the people at WWE, we’re always paying attention to what’s going on. But when, I don’t know. I hope there’s a time where I can really get ready, like I did the last few times. And I’d love to take more time to get ready physically.

But man, just like in music, I do this to get better and to do something different. Sometimes, I say, “I’m going to quit everything and just do wrestling full time.” I feel like in wrestling, I just go sporadically as a celebrity. I’m going to go full time and be a heel. That’s what I’d love. [Laughs.] I was always a fan of the villains more than the good guys.

What was it like to bring WWE’s Backlash event to Puerto Rico?

What can I tell you? It was nice. We were there until we could bring WWE to Puerto Rico. And man, I actually feel like it was good for them and for everyone, because I saw that last year Backlash was in France, now it’s going to Mexico. They saw that it worked.

As you’ve gotten more famous, your love life has become more public. How does it feel knowing that any song you release about heartbreak is going to be analyzed line by line as fans try to figure out who it’s about?

When everything is said and done, I know that’s going to happen. The truth is, it doesn’t bother me. I know that’s part of the process. If I say something and people know I’m expressing myself, I know they are going to look for associations. I think it’s funny when they’re completely wrong. I’m like, “Man, why would you even think of that?” Sometimes, there’s zero reasoning for the things they come up with.

But I’ve always said this, and I don’t know if it’s fair to say, but I think there’s a difference between dedicating a song [to someone] and being inspired by someone. Like, I can make this song inspired by what I lived through and what happened, because it’s my experience and it belongs to me. What I lived through belongs to me and the other person, so I think I’m allowed to express myself and tell it the way I want to: I can add something, I can take something away. But if I’m writing a song about a situation I went through, it doesn’t mean that I’m dedicating that song to that person. That’s the difference. People can get confused — even the person it’s about can get confused and be like, “Oh, this song is for me!” No, it’s not for you. It’s about you, but it’s not for you. But sometimes it is [laughs].

Has fame affected you as a songwriter? Are you thinking about these things when you’re writing?

Honestly, no. I don’t think about it too much. Or I do think about it, and it does worry me sometimes, but I don’t let that limit me from writing what I want and being honest with myself and with people in my songs. I prefer that over making stuff up.

Photograph by Christopher Gregory-Rivera

There’s a lot of nostalgia and sadness in your music sometimes.

There’s nostalgia and sadness. People are going to complain about me and be like, “This guy cries too much!” [For the song “Turista”], I was in Puerto Rico, and I got out of the office and I started just circling around Ocean Park. In that moment, I was so sad. I was crying, and I had so many things on my mind.

Why were you crying? What happened to you?

I got bit by a mosquito [smiles]. I went by the beach, and I saw all these tourists taking dance lessons and playing volleyball and taking selfies by the sunset, and I was like, “Wow.” It made my head explode that I was in the car, so sad, and these people were so close to me and so happy, and they had no idea I was passing by all sad. And that happens. Right now [in this room], there could be someone who’s very sad and we don’t know it. But that blew my mind, and part of what I was thinking about was the situation in [Puerto Rico] as well. I was like, “These people are here watching this incredible sunset, they’re taking beautiful fucking photos, they’re having the best time.” They’re gonna leave and they enjoyed the best of Puerto Rico, but they didn’t actually live through what Puerto Ricans go through every day, the negative parts of the country, the situations Puerto Ricans live day by day. So, I parked the car and I started writing a song with this idea of “In my life, you were just a tourist.” Like, there are people who come into your life, and they enjoy the best of you, the nice version from the first few months, and then they leave. But they didn’t get to know me deep down, my anxieties, my fears, my sadness, my traumas.

You bought billboards across San Juan to protest the New Progressive Party ahead of the island’s gubernatorial election in November. You also spoke at a rally to support the third-party pro-independence candidate Juan Dalmau. You’ve always talked about Puerto Rico in your music, but what made you want to be more vocal, especially ahead of the elections?

I think I’ve always done it in a natural way. But the more pissed I am, the more I’m going to yell. I’ve always made it clear to people that I’m a real person, and my music reflects that. I’m a real person, a Puerto Rican who is 30 years old, and my entire career, no matter what position I’m in, this is what I am and that’s what my music is about. I make songs about heartbreak, about perreo, and about social issues because this is what I’m like, as well as so many other people. It’s not like we’re always just hanging out Friday, Saturday, Sunday. On Monday, you have to go to work. So that’s how I express myself. When it’s time to party and talk about ass and pussy and all that, you do that. When I’m sad about love, I say that. But when something makes me mad … That happens a lot. But you can’t complain all the time, and our personal life takes us out of that — relationships, your significant other, all of that takes you out of the social issues sometimes. So that’s how I work.

The elections are every four years, but it’s not something we only talk about every four years. We’ve always been vocal when we need to be. I think people get surprised that I’m at this level of popularity and I’m mainstream, but I don’t think twice when it comes to expressing myself. But that’s what makes me human. I think people are used to artists getting big and mainstream and not expressing themselves about these things, or if they do, talking about it in a super careful way. But I’m going to talk, and whoever doesn’t like it doesn’t have to listen to me. Or you can keep listening to me and I can think differently from you — we all live in the same country. And that’s something I’ve said: Politicians take advantage of situations to divide people, and that’s never been my goal. And I’ve never been scared to express myself, because that’s who I am, cabrón.

When you spoke at Dalmau’s rally, you said giving political speeches made you more nervous than performing.

I’m shy to a point. Once I’m comfortable with people, I’m a crazy person. But in the beginning, I’m always shy, and when it comes to talking about stuff like that, I get super nervous, especially if it’s an environment that’s not my concert. If it’s my concert, if it’s my stage, I do whatever I want. But if I have to go somewhere else and speak, it’s really hard. It’s hard for me to even make a toast. I’m like, [voice shakes] “Blessings, everyone!” So to talk about such a personal and serious situation in a place where there were so many people, I knew every word was going to last forever. I was super nervous, but I also felt great after I did it.

How do you stay hopeful? The elections in Puerto Rico and in the U.S. didn’t turn out the way a lot of people wanted them to.

I think we’re used to this by now. At the end of the day, in an election, there’s someone who wins and someone who loses. But this is not the first time or something new. I just think people had a lot of hope this time around, and that’s why it felt like such a blow. But it isn’t new for us to have to keep moving and going with our lives and to keep fighting and to keep resisting and to keep defending what’s ours.

“IN THAT MOMENT, I WAS SO SAD. I WAS CRYING, AND I HAD SO MANY THINGS ON MY MIND.”

Recently, someone asked me what message I’d give the day before and the day after [the elections], and it would be the same one. The situation doesn’t change, but that keeps creating social consciousness and strength.

You’ve always represented Puerto Rico, no matter the stage you’re on. At the 2023 Grammys, for example, you had bomba and plena dancers join you onstage. What’s it like to be able to share those traditions with the world?

It makes me feel proud and happy with myself. I love doing this. I love making music. I always dreamed about people listening and recognizing my music, and to be able to make a living from it. But even though I dreamed about it deep in my heart, I never expected to get to this level so far. So I started asking myself, “What’s next? What do you keep doing?” I don’t ever try to break some record I already broke or to do better than who knows what. With [each album], I’m not trying to do better than Un Verano Sin Ti or YHLQMDLG — nothing. I want to create something new. Different memories, different records — something different than what I made before.

So what else do I want to do? What’s the point in being here? What’s the point of being at this level? What do I win? I’ll die and that’s it — I’m not going to take anything with me. So I think that’s it: to show the world who I am and what my culture is, where I grew up. To talk a little about myself so they can get to know me a little more, and that’s me: I’m Puerto Rican. To be able to put this genre in a high position, to put these artists in a high position.… They’re making music the same way I did, without expecting anything, and just out of the sheer pleasure and passion of making music, and to share a message with other people. At this point, that’s what fills me up: to be able to help and to give a position to different rhythms and young people like me.

You’ve said in the past that you’re always working years ahead and that you have your next few albums planned out. How do those projects change once you start working on them?

Yeah, it changes. With [Debí Tirar Más Fotos], I had the initial idea, but it changed for the better, in my opinion. It started picking up its own personality and energy, its own flow. Actually, when I was making Nadie Sabe Lo Que Va a Pasar Mañana, I wanted to start working on this. I don’t want to be mean to [that album], but I feel like it was the one I enjoyed the least, in the sense that I put pressure on myself to make it. When I went on tour for Nadie Sabe Lo Que Va a Pasar Mañana, it was the same thing — I was like, “I don’t want to tour. I want to work on a new album.”

Why did you feel so much pressure with Nadie Sabe Lo Que Va a Pasar Mañana?

I put that into my own head. I was like, “I want to release an album that’s only trap and this type of music.” There’s a moment when you go on these head trips, like, “This is what people want.” But what people? Right now, we’re sitting in this office, and I feel like this album is everything, and everything happening in here is everything. But if you take Google Maps [pulls up Google Maps and zooms out into a view of the whole world], we’re nothing. My album is nothing, I’m nothing. So, who the hell is listening? And what’s the pressure I’m giving myself? You learn from things. I love that album, but I learned where I want to be and where I want to go. I’m going to be where I’m comfortable and happy and where I feel like I’m adding something.

Un Verano Sin Ti broke a bunch of records. Did you see that album going as far as it did when you were making it?

No, man. I think you make these projects hoping they’ll be a success, and that people will like them. But to that extreme magnitude, no. I thought it would be a little less [laughs]. I did have some confidence when I was making it — I remember I used to say to my manager, Noah, “I’m making this album. Please work it well.” I don’t repeat formulas. I can repeat certain things, but not a whole formula, no. So I knew I was making an album that was rich in terms of everyone liking it. I said, “Take advantage, because after this one, I’m not making another one like it.” I knew it would have success, but I didn’t think it would happen the way it did.

I also wasn’t looking for that. I wanted to create certain sounds and for people to listen to it from beginning to end and for everyone to have a favorite song. I always said that [about Un Verano Sin Ti]: There’s a song for everyone. But I never guessed it would get to the level it did. And at the end, I’m happy and proud because that was the goal: for people to like it. But now Un Verano Sin Ti is there, and I’m never looking to surpass Un Verano Sin Ti. My next projects aren’t about getting it to the same level or surpassing it, no. That’s there and I made it. It’s time to make other things, and I’m happy with that.

Do you see yourself doing this until you’re an old man?

Bro, yes, from the heart. Sometimes I say, “Damn, I think I’m going to stay here, finding the rhythms I like and what fills me.” I’ve always said I love percussion — drums, conga, bongos. There’s something in me that’s always loved that. I think there’s something in my DNA that’s calling me. And I loved making [Debí Tirar Más Fotos]. The album I enjoyed making the most, out of all of them, was this one.

Did you take more photos this time?

[Laughs.] I took a few.

Production Credits

Styling by STORM PABLO. Styling assistance by MARVIN LINARES. Grooming by CHRISTOPHER DILÁN. Set design by ANDREA GANDARILLAS PÉREZ. Photographic assistance by SANGWOO SUH. Digital tech: BEN HOSTE. Set dresser: JAFET MARQUEZART.